By Alan Hess

By Alan Hess

The PLF blog will feature a series of posts exploring modernist sites and efforts to preserve them. Join our top-notch blog contributors as they take you from Tucson’s Sunshine Mile to Googie coffee shops. We think you will enjoy the journey.

Before you can preserve a building, you have to be able to see it.

In Modern architecture, though, there are a lot of examples we have trouble seeing. Modernism (that explosion of experiment in the 20th century that dramatically changed the materials and shapes of buildings) generated dozens of variations and ideas during a period of economic and population growth. So far we have focused mostly on a narrow portion of them: the flat-roofed, steel and glass boxes. But what about the curves of a house by John Lautner? The pyramids of William Pereira? The slanting shed roofs of Sea Ranch by Moore/Lyndon/Turnbull/Whitaker? The interlocking spaces in a Paul Rudolph building? The shimmering pavilions of Minoru Yamasaki?

To one degree or another, these buildings were not seen for many years, even though they were there. It took a conscious effort to see them, to understand them—and to bring them back into our awareness as part of our heritage.

To one degree or another, these buildings were not seen for many years, even though they were there. It took a conscious effort to see them, to understand them—and to bring them back into our awareness as part of our heritage.

How do buildings become invisible? There are many ways: they don't fit the conventional definition of Modernism; the reputation of their architects has fallen off the radar screen; they were the buildings of common everyday life, rather than the exquisite palaces of noted museums, major corporations, or famous fashionistas.

Let's take a closer look at one of these unseen building types: the Googie coffee shop. It's gone full circle; we can now trace its path from notoriety to invisibility, and back to awareness and even successful preservation.

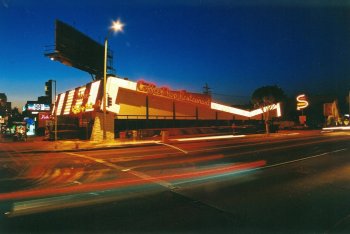

We'll take one example, Johnie's Coffee Shop at Wilshire and Fairfax in Los Angeles, designed in 1955 by architects Armet and Davis. Last year it surmounted all odds to become an official Los Angeles city landmark.

If it's daytime, the first thing you notice about Johnie's is its enormous asymmetrical butterfly roof. Its ends turn down as a sunshade to screen the sidewalk-to-ceiling glass walls that enclose two sides of the restaurant. If it's nighttime, the first thing you notice is its brilliant, jaunty neon sign, integral with the roof.

Buildings this angular, bold, glassy, and bright were clearly Modern, but they did not fit into any conventional category when they began to appear on the nation's streets after World War II. A word had to be invented to describe them; editor Douglas Haskell of House and Home magazine anointed them as Googie in 1952, named after a coffee shop with that name on the Sunset Strip by John Lautner.

The word worked. This type of building became visible. But not for long.

The word worked. This type of building became visible. But not for long.

Yet the public flocked to Johnie's and other similar coffee shops that spread nationwide for all the right reasons: decent food at a good price, yes, but also for its design and planning, the convenience of the location on major thoroughfares, the ease of access from the parking lot, the spacious light-filled patio-like seating areas, the liveliness of the social setting, the excitement of progressive design in tune with its times. As American cities stretched and grew into suburban metropolises, Googie was a new architecture that suited it well.

For critics, however, the silliness of the name implied a lack of conceptual seriousness. That inference was often rooted in class issues: Googie was used for everyday commercial buildings like coffee shops, gas stations, car washes—places where average people went about their daily lives. These were not considered “important” buildings, so they could not be important designs.

While its bold, large-scale form followed its function by advertising the restaurant to motorists driving by, critics enamored of minimalism and Miesian details didn't get it. The word Googie came to be associated with exaggeration, superficial effect, and selling—not the refined Modernism of the Seagrams building. It was “suburban, ” “merely” commercial, “only” advertising, “just” a coffee shop, not “real” architecture.

Words like that made Googie coffee shops invisible again for 30 years. Examples were demolished, their memory forgotten—until Googie was rediscovered, and the scarce examples remaining were landmarked and restored. Besides Johnie's, Bob's Big Boy in Toluca Lake, Calif., (1949, Wayne McAllister, architect), Harvey's Broiler in Downey, Calif., (1956, Paul Clayton, architect), and the second golden-arched McDonald's in Downey, Calif., (1953, Stanley Meston, architect) have been landmarked. Today Googie is a distinct and significant part of the story of Modernism telling how it became part of the everyday life of millions. And as a piece of urban design, Johnie's still holds its corner as confidently as ever.

Many other facets of Modernism have gone—or are going through—similar cycles of neglect and rediscovery. The distinctive work of maverick architects like John Lautner and Paul Rudolph, the alternative Modernisms of Minoru Yamasaki and Edward Durell Stone, the mainstream Modern highrises and campuses of William Pereira: each journey requires us to see how they expressed Modernism, urbanism, and culture in the 20th century.

But like the critics who could not see Googie as architecture, we have to overcome the biases that keep them invisible before we can save them.

That may be the biggest obstacle of all. Our well-educated opinions are often the things that keep us from seeing significant trends and buildings. But consider this: it is often the buildings that make us most uncomfortable, that we least want to look at, that best capture the true nature of an era—and so are most significant historically. The stark haughtiness of Paul Rudolph's Yale School of Architecture, the exuberant swoop of a 1959 Cadillac tail fin: such controversial designs capture the lightning of midcentury Modern design.

The buildings that we most resist exploring (or preserving) may be the ones that we most need to look at. Their design solutions can play a role in making the city of today stronger and ultimately more livable.

RELATED VIDEO