|

Richard Neutra The life of no other 20th-century architect so epitomized the term International Style as that of Richard Neutra (1892-1970), who gained worldwide recognition as an advocate of modern design. In the United States, he had a strong influence on architecture, particularly in California. In 1922 he came to America, where he worked briefly for Frank Lloyd Wright (1867-1959) at Taliesin and for Holabird and Roche in Chicago, an experience that formed the subject of his first book, Wie Baut Amerikal, published in Stuttgart in 1927. His design for the Lovell (Health) House (1929), Los Angeles, with balconies suspended by steel cables from the roof frame, was, in retrospect, one of the most important works of his career. The open-web skeleton was transported to the steep hillside by truck. When the house was featured in Neutra's second book, Amerika, published in Vienna in 1930, he was hailed as a technological wizard. He returned to Europe in 1930 and was asked to lecture at the Bauhaus and in Japan. Neutra's architecture was usually rectangular and straight-lined, unmistakably man-made, yet always sensitive to the site. The years before World War II saw the completion of the Beard House (1934), Altadena, and the country house for Joseph von Sternberg (1935), San Fernando Valley: both made from the latest prefabricated steel sandwich panels. His later public buildings never gained the recognition of his earlier domestic designs. Ludwig Mies van der Rohe Mies van der Rohe, the third and final head of the Bauhaus school, emigrated to Chicago in 1938, where he became director of architecture at the Armour Institute in Chicago (now the Illinois Institute of Technology, IIT). He also started his own thriving practice as an architect. Such was his energy and innovation, that by the late 1940s he had become a highly influential mentor to a generation of students as well as professional designers within large firms such as Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, C.F.Murphy & Associates, and others. He and his followers, collectively known as the Second Chicago School of architecture (c.1940-75) are most clearly identified with glass-and-steel skyscrapers such as the Lake Shore Drive Apartments (1948-51) Chicago; the lavish Seagram Building (1958) New York, designed in collaboration with the interior design of Philip Johnson; the IBM Building (1971) (now 330 North Wabash) New York. Followers of Mies included former IIT students, such as Jacques Brownson (1923-2011), who designed the Richard J. Daley Civic Center (Daley Plaza) (1965) in Chicago, as well as George Schipporeit and John Heinrich who designed Lake Point Tower (1968), Chicago. International Style in America: Second Chicago School In the 1930s, with the emigration of intellectual leaders like Gropius and Mies van der Rohe, along with other Bauhaus modernists like Laszlo Moholy-Nagy (1895-1946), the International Style spread from Germany and France to North America, Scandinavia and Britain. In America, thanks largely to Mies and the Second Chicago School, including Skidmore, Owings & Merrill and brilliant structural engineers like Fazlur Khan (1929-82), the clean, streamlined, geometric attributes of the International Style came to dominate the skyscraper architecture during the 1950s and 1960s, in an era when corporate modernism and cost-benefit analysis were high fashion. Thus the International Style provided the aesthetic rationale for the inexpensively surfaced tower buildings that became the status symbols of American corporate power during this period. Philip Johnson Johnson has had a profound impact on American architects for more than six decades. In the 1930s as an architectural historian, he helped introduce modern architecture - the glass box - to America with a book and exhibit on the International Style at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, where he was director of the architecture department. In the 1940s Johnson the historian became Johnson the architect, and built what is perhaps the country's most famous modern house, the Glass House (1949), his own residence in New Canaan, Connecticut. In the 1950s he collaborated with Ludwig Mies van der Rohe on the design of the landmark Seagram Building (195458) in New York. However, just as the International Style was reaching its zenith, Johnson began to speak out against its purist aesthetic. "You cannot not know history, " he told students at Yale University, who had been taught by their devout modernist instructors to ignore the past. In the 1960s he began to invest his modern buildings with historical references, as with the Ottoman Empire-inspired Museum for Pre-Columbian Art (1963) at Dumbarton Oaks, Washington DC. In the 1970s and 1980s the man who introduced the glass box became the one to break it, with his IDS Tower (1972) Minneapolis, noted for its distinctive stepbacks, or "zogs"; and his AT&T Building in Manhattan (1984) (now the Sony Building), famous for its neo-Georgian pediment (Chippendale top), which contradicted every precept of the International Style. Johnson's move away from the International Style brought professional respectability to Postmodernism. Decline By the 1970s, the International Style was so dominant that innovation was dead. Mies continued to design beautiful buildings, but was copied everywhere. As the saying went: "You got off an airplane in the 1970s, and you didn't know where you were." As a result, many architects felt dissatisfied with the limitations and formulaic methodology of the International Style. They wanted to design buildings with more individual character and with more decoration. Modernist International Style architecture had removed all traces of historical designs: now architects wanted them back. All this led to a revolt against modernism and a renewed exploration of how to create more innovative design and ornamentation. As Postmodernism took hold, building designers began creating more imaginative structures that employed modern building materials and decorative features to produce a range of novel effects. By the late 1970s, modernism and the International Style were finished. Famous International Style Buildings Among the most iconic examples of the International Style of architecture are the following: - The Fagus Factory (1911-25) Alfeld on the Leine (Gropius)

19th Century American Architects For... |

RELATED VIDEO

Mid-Century modern is an architectural, interior, product and graphic design that generally describes mid-20th century developments in modern design, architecture, and urban development from roughly 1933 to 1965. The term, employed as a style descriptor as early as...

Mid-Century modern is an architectural, interior, product and graphic design that generally describes mid-20th century developments in modern design, architecture, and urban development from roughly 1933 to 1965. The term, employed as a style descriptor as early as...

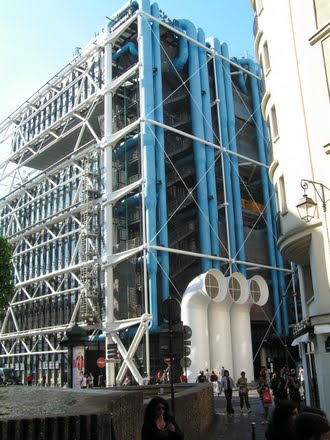

High-tech architecture, also known as Late Modernism or Structural Expressionism, is an architectural style that emerged in the 1970s, incorporating elements of high-tech industry and technology into building design. High-tech architecture appeared as a revamped...

High-tech architecture, also known as Late Modernism or Structural Expressionism, is an architectural style that emerged in the 1970s, incorporating elements of high-tech industry and technology into building design. High-tech architecture appeared as a revamped...