An ancient classic

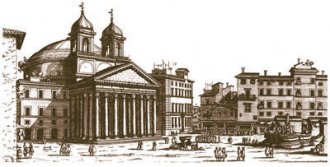

Michelangelo (1475-1564) looked at everything with an artist’s critical eye, and he was not easily impressed. But when Michelangelo first saw the Pantheon in the early 1500s, he proclaimed it of “angelic and not human design.” Surprisingly, at that point, this classic Roman temple, converted into a Christian church, was already more than 1350 years old.

What’s even more surprising is that the Pantheon, in the splendor Michelangelo admired, still stands today – another 500 years after he saw it.

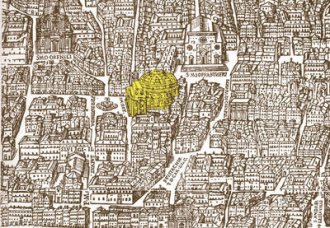

In truth, no one knows the Pantheon’s exact age. One legend says that the first Roman citizens built the original Pantheon on the very site where the current one still stands in the Campo Marzo – modern Rome’s business district. The ancients constructed this first Pantheon after Romulus (753-716 BC), their mythological founder, ascended to heaven from that site. They dedicated it to Romulus and some of his divine ancestors and, for centuries, held rites and processions there.

Most historians, however, claim that Emperor Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa built the first Pantheon in 27 BC, a rectilinear, T-shaped structure, 144 feet by 66 feet (44m x 20m), with masonry walls and a pitched timber roof. It burned in the great fire of 80 AD, was rebuilt by Emperor Domitian, but was struck by lightening and burned again in 110 AD.

Most historians, however, claim that Emperor Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa built the first Pantheon in 27 BC, a rectilinear, T-shaped structure, 144 feet by 66 feet (44m x 20m), with masonry walls and a pitched timber roof. It burned in the great fire of 80 AD, was rebuilt by Emperor Domitian, but was struck by lightening and burned again in 110 AD.

An elegant emperor

Seven years later, Hadrian, the adopted son and successor of Emperor Trajan, became Rome’s ruler. Hadrian was elegance personified. He was tall and strong, had his hair curled and his full beard groomed daily. Moreover, Hadrian saw himself as a divinely inspired poet, with an avid interest in Hellenic culture, especially literature, music and architecture – so much so that his contemporaries snidely called him “the Greekling.”

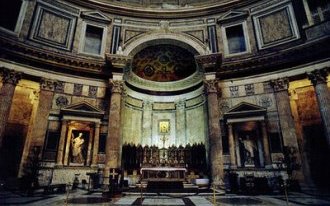

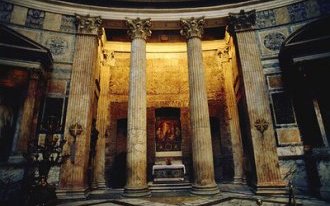

By 120 AD, Hadrian began designing a Pantheon reminiscent of Greek temples and far more elaborate than anything Rome had yet seen. His plans called for a structure with three main parts: a pronaos or entrance portico, a circular domed rotunda or vault, and a connection between the two. The rotunda’s internal geometry would create a perfect sphere, since the height of the rotunda to the top of its dome would match its diameter: 142 feet (43.30 m). At its top, the dome would have an oculus or eye, a circular opening, with a diameter of 27 feet (8.2m), as its only light source.

Hadrian said, “My intentions had been that this sanctuary of All Gods should reproduce the likeness of the terrestrial globe and of the stellar sphere…The cupola…revealed the sky through a great hole at the center, showing alternately dark and blue. This temple, both open and mysteriously enclosed, was conceived as a solar quadrant. The hours would make their round on that caissoned ceiling so carefully polished by Greek artisans; the disk of daylight would rest suspended there like a shield of gold; rain would form its clear pool on the pavement below, prayers would rise like smoke toward that void where we place the gods.”

Hadrian said, “My intentions had been that this sanctuary of All Gods should reproduce the likeness of the terrestrial globe and of the stellar sphere…The cupola…revealed the sky through a great hole at the center, showing alternately dark and blue. This temple, both open and mysteriously enclosed, was conceived as a solar quadrant. The hours would make their round on that caissoned ceiling so carefully polished by Greek artisans; the disk of daylight would rest suspended there like a shield of gold; rain would form its clear pool on the pavement below, prayers would rise like smoke toward that void where we place the gods.”

Hadrian visualized himself enthroned directly under the Pantheon’s oculus – a near-deity around whom not only the Roman empire but the universe, the sun, and the heavens obediently revolved.

Work begins

Hadrian’s engineers began clearing the site and preparing the foundations. They dug a circular trench 26 feet (8 m) wide and 15 feet (4.5 m) deep for the rotunda’s foundation and rectangular trenches for the pronaos and the connector. They lined the trenches with timber forms and layered those with pozzolana cement – a powerful cement that the Romans discovered they could make by grinding together lime and a volcanic product found at Pozzuoli, Italy.

Hadrian’s engineers began clearing the site and preparing the foundations. They dug a circular trench 26 feet (8 m) wide and 15 feet (4.5 m) deep for the rotunda’s foundation and rectangular trenches for the pronaos and the connector. They lined the trenches with timber forms and layered those with pozzolana cement – a powerful cement that the Romans discovered they could make by grinding together lime and a volcanic product found at Pozzuoli, Italy.

Though the Romans had been building with concrete since about 200 BC, work on the Pantheon was difficult and proceeded in gradual stages. Other buildings surrounded the site so laborers lacked space in which to work.

They also lacked machinery. Vitruvius (cir. 20 BC), a noted Roman architect, recorded the process followed in his day, that was probably still used by the Pantheon’s builders. The ancients hand mixed wet lime and volcanic ash in a mortar box, adding very little water so that they got a nearly dry composition. They carried this mixture to the jobsite in baskets and poured it over a prepared layer of rock pieces. They then tamped the mortar into the rock layer. The tamping packed the mortar, reduced the need for excess water, but, at the same time, stimulated bonding.

Transportation presented another problem. Just about everything had to come down the Tiber by boat, including the 16 gray granite columns Hadrian ordered for the Pantheon’s pronaos. Each was 39 feet (11.8 m) tall, five feet (1.5 m) in diameter, and 60 tons in weight. Hadrian had these columns quarried at Mons Claudianus in Egypt’s eastern mountains, dragged on wooden sledges to the Nile, floated by barge to Alexandria, and put on vessels for a trip across the Mediterranean to the Roman port of Ostia. From there the columns were barged up the Tiber.

A concrete dome

Eventually, work began on the concrete dome, constructed in tapering courses or steps that are thickest at the base (20 feet) and thinnest at the oculus (7.5 feet). The Romans used the heaviest aggregate, mostly basalt, at the bottom and lighter materials, such as pumice, at the top.

They embedded empty clay jugs into the dome’s upper courses to further lighten the structure and facilitate the concrete’s curing.

In the dome’s construction, the Romans probably used temporary wooden centering on which they layered concentric rings of masonry and concrete.

RELATED VIDEO

The Janiculum (Gianicolo in Italian) is a hill in western Rome, Italy. Although the second-tallest hill (the tallest being Monte Mario) in the contemporary city of Rome, the Janiculum does not figure among the proverbial Seven Hills of Rome, being west of the Tiber...

The Janiculum (Gianicolo in Italian) is a hill in western Rome, Italy. Although the second-tallest hill (the tallest being Monte Mario) in the contemporary city of Rome, the Janiculum does not figure among the proverbial Seven Hills of Rome, being west of the Tiber...