The Past That Never Dies

by Mary Miley Theobald

The past is never dead. It isn’t even past.—William Faulkner

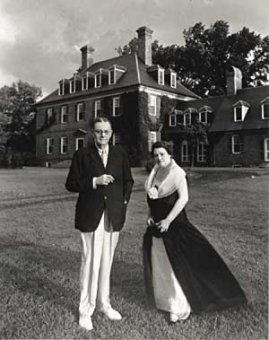

Courtesy of Su Carter

At the peak of the Colonial Revival, antiques that had arrived on the Mayflower seemed so common that the ship must have been awash in furniture, as suggested by this F. Opper cartoon in Bill Nye’s 1894 History of the United States.

Preservation feaver swept America in the 1920s. Virginia, with more colonial buildings than most states, was hard hit. Private individuals and preservation societies snapped up derelict plantation homes and restored and furnished them for personal use or to open to the public. In Virginia, Monticello, Stratford Hall, Montpelier, Oak Hill, Brandon, Kenmore, Ampthill, Carter’s Grove, and dozens more were saved from ruin. Creating museums from historic buildings became a preferred philanthropy for the wealthy: in Michigan, Henry Ford started Greenfield Village; in Delaware, the DuPonts began transforming Winterthur inside and out. And John D. Rockefeller Jr. launched the largest single preservation project the country had seen: Colonial Williamsburg.

Symptoms of the preservation epidemic had begun to appear as early as the 1840s. “Fashion has taken up antiquity, ” wrote a member of the American Antiquarian Society in 1842. “Old pictures, old furniture, old plate and even old books which have heretofore suffered neglect . . . are now sought with eagerness as necessary adjuncts of style.” New York’s Metropolitan Museum, which had validated the collecting impulse in 1909 with the first exhibit devoted to American furniture, opened in 1924 an American Wing with period rooms full of American antiques. By the Roaring Twenties, collecting had transcended objects. For those who could afford it, an antique house—restored, modernized, and appropriately furnished—became the ultimate fashion statement.

Historic preservation formed the core of the Colonial Revival, a social and stylistic mindset that peaked during the 1920s. At its start, the Colonial Revival was a social movement that looked to a romanticized past for inspiration and answers to modern problems. When architects hijacked the movement in the 1880s, the focal point became the home. The style has dominated the American landscape since, sometimes sharing the scene with other fashions but never shrinking far into the distance.

Historic preservation formed the core of the Colonial Revival, a social and stylistic mindset that peaked during the 1920s. At its start, the Colonial Revival was a social movement that looked to a romanticized past for inspiration and answers to modern problems. When architects hijacked the movement in the 1880s, the focal point became the home. The style has dominated the American landscape since, sometimes sharing the scene with other fashions but never shrinking far into the distance.

Historians, architects, and curators are interested in the Colonial Revival phenomenon. Most date its start to the Philadelphia Centennial Exposition in 1876. Thus an exhibition celebrating the miracles of modern industry launched a movement glorifying the past. Its most popular attraction was Machinery Hall, with the latest technological wonders—the typewriter, the telephone, and the refrigerated railroad car. But the show marked the nation’s one-hundredth birthday, and it was in the city deemed sacred for its association with the Declaration of Independence. The thoughts of the ten million people who visited the fair turned to the past.

Colonial Williamsburg

Wealthy Archibald and Molly McCrea, pictured in 1936, had the means to indulge themselves in all things colonial, including the restoration of the sprawling Carter’s Grove mansion.

The 1870s were troubled. Hard on the heels of Civil War carnage and Reconstruction turmoil came economic depression. Rampant corruption in Washington outraged decent citizens. Striking union workers, Chinese laborers, and emancipated African Americans suffered violent suppression. Custer rode into the valley of the Little Bighorn River.

By the 1880s and 1890s, boatloads of immigrants docked in northern ports, immigrants from eastern and southern Europe whose religions and traditions were vastly different from most native-born Americans’. Industrialization and urban growth threatened agrarian patterns. The European cauldron of revolutions, riots, and anarchist uprisings was spilling onto United States shores. “The influx of foreign ideas utterly at variance with those held by the men who gave us the Republic, threaten, and unless checked, may shake the foundations” of the country, wrote R. T. H. Halsey, a leader of the Colonial Revival movement. To Americans descended of earlier stock, the real America was under siege.

By the 1880s and 1890s, boatloads of immigrants docked in northern ports, immigrants from eastern and southern Europe whose religions and traditions were vastly different from most native-born Americans’. Industrialization and urban growth threatened agrarian patterns. The European cauldron of revolutions, riots, and anarchist uprisings was spilling onto United States shores. “The influx of foreign ideas utterly at variance with those held by the men who gave us the Republic, threaten, and unless checked, may shake the foundations” of the country, wrote R. T. H. Halsey, a leader of the Colonial Revival movement. To Americans descended of earlier stock, the real America was under siege.

Unsettled times often encourage people to turn to the past. Americans of the late nineteenth century had only to look back one hundred years to see an era that by comparison looked idyllic: a Golden Age of American values, when heroic pioneers sustained their families through honest labor and patriotic farmers fought for freedom beside selfless Founding Fathers. The vision was not so much inaccurate—there were heroic pioneers and selfless Founding Fathers—as it was incomplete and romanticized. But it was a vision widely shared. People pined for good old days when life was simple, friendships true, and everyone lived in rooms full of Queen Anne furniture.

In the public’s mind, America’s Golden Age stretched from the day the Pilgrims set foot on Plymouth Rock—never mind the earlier settlement at Jamestown; this was a northern vision—to the death of the last two Founding Fathers in 1826. People referred to the period as “colonial” though it stretched fifty years past the nation’s birth. So too with furniture: Federal, Heppelwhite, and Sheraton pieces made in the early 1800s were considered as colonial as William and Mary or Chippendale.

Reviving all things colonial seemed the obvious antidote to the nation’s ills. By preserving, exhibiting, collecting, and reproducing the colonial, Americans would be inspired to higher degrees of patriotism. Thomas Jefferson agreed. During the last year of his life he wrote, “Small things may perhaps, like the relics of saints, help to nourish our devotion to this holy bond of our Union.” By the 1890s the Colonial Revival dominated the northeastern seaboard and was spreading south and west. The flood of immigrants had become a tidal wave. Americans everywhere gloried in their heritage even as they worried about its endurance.

The movement’s strongest and earliest proponents were, not surprisingly, men and women whose pedigrees stretched to colonial days. These were people whose ancestors led the country and who were leaders themselves, but whose dominance of the political, economic, and social scenes was waning. Genealogical societies sprang up like crocuses in February as scions of colonial families flaunted their superiority over recent arrivals. Heritage groups were founded: the Sons of the Revolution in 1883, the Sons of the American Revolution in 1889, and the Daughters of the American Revolution in 1890, when the Sons rejected female members. Following quickly were the National Society of Colonial Dames, the Colonial Dames of America, the General Society of Colonial Wars, the Children of the American Revolution, the Society of Mayflower Descendants, and three dozen others, most now defunct.

RELATED VIDEO

The Spanish Colonial Revival Style was a United States architectural stylistic movement that came about in the early 20th century, starting in California and Florida as a regional expression related to history, environment, and nostalgia. The Spanish Colonial...

The Spanish Colonial Revival Style was a United States architectural stylistic movement that came about in the early 20th century, starting in California and Florida as a regional expression related to history, environment, and nostalgia. The Spanish Colonial...

The Spanish Empire (Spanish: Imperio Español) comprised territories and colonies administered by Spain in Europe, the Americas, Africa, Asia and Oceania. It originated during the Age of Exploration and was one of the first global empires. At the time of Habsburgs...

The Spanish Empire (Spanish: Imperio Español) comprised territories and colonies administered by Spain in Europe, the Americas, Africa, Asia and Oceania. It originated during the Age of Exploration and was one of the first global empires. At the time of Habsburgs...