Harkness Tower, on the campus of Yale (Avinash Godbole/Flickr)

Harkness Tower, on the campus of Yale (Avinash Godbole/Flickr)

The campus of Yale University, 1921. Midnight.

It is perhaps the most important job of your career. You, a successful architect, have been selected by a rich donor to build a new tower here, on your alma mater’s campus, at Yale. The tower, Gothic in style, named “Harkness, ” must look archaic, timeless. It is 216 feet tall, one foot for every year since Yale’s founding. You could be building history…except that the tower does not look nearly old enough.

So you—in, presumably, a long cape, high collar, and top hat—sneak to the construction site. You pull a flask from the folds of your garment, uncork it—and throw acid onto the new granite.

The rock wears away, shows pockmarks, ages.

You have done it. You are a genius.

***

We know what elite American colleges should look like. Tall Gothic towers, Georgian angles and radii, and the few massive, newer slopes of Cold War modernism: It’s a collage recognizable as “college.”

A rainbow over Princeton University’s Chapel. The chapel is the the last Gothic structure built on campus in the 20th century. (Flickr/schizoform) But American schools didn’t always look this way. A little more than a century ago, there was no cachet in being an “old college, ” and there was little cachet, too, in having the old architecture to match it. But a combination of forces—some cultural, some economic—transformed the appearance of American institutions, and made the modern-day college campus take its contemporary appearance and mythology.

But American schools didn’t always look this way. A little more than a century ago, there was no cachet in being an “old college, ” and there was little cachet, too, in having the old architecture to match it. But a combination of forces—some cultural, some economic—transformed the appearance of American institutions, and made the modern-day college campus take its contemporary appearance and mythology.

How did that happen? Who was responsible? And did a caped geometer ever toss potent hydrochloric onto a trademark New Haven edifice?

In 1888, according to historian John Thelin, administrators from the College of William & Mary came before the Virginian legislature to plead for a more stable source of funding. They argued the college’s long history earned it a bail-out in cash-poor times. The College was older than the nation: Surely this meant something.

It didn’t. The state’s General Assembly was unmoved by the college’s appeal, and elected instead to subsidize it every year.

It didn’t. The state’s General Assembly was unmoved by the college’s appeal, and elected instead to subsidize it every year.

Why did it neglect to fund the school in a more long-term way? Because, to the state, the College was less a historical treasure, and more a tool which could provide a very specific service. As Thelin writes, the Assembly’s main goal was “educating a cohort of white male schoolteachers to staff the state’s emerging public school system.”

Maybe that’s not a revealing story: State legislatures still fund schools too little and on a year-by-year basis. A half-century later, though, colleges would stake their case to donors and future students on their own long history, deep tradition and historical importance. An old university was patriotic: As Thelin writes, “Our oldest corporation … is Harvard College, not a commercial business.”

The Wren Building, on William & Mary’s campus, a building not at all in the Gothic style (Flickr/Lane 4 Imaging) As for William & Mary’s patriotic appeal, perhaps it came a year or two too early. Thelin tracks the birth of patriotic feeling to the American centennial in 1876, and the flurry of centennials that followed it. The 1889 centennial of George Washington’s inauguration in particular spurred the formation of the Daughters of the American Revolution. Its membership ballooned in the 1890s, and it did much to boost people’s recognition of patriotism and history.

As for William & Mary’s patriotic appeal, perhaps it came a year or two too early. Thelin tracks the birth of patriotic feeling to the American centennial in 1876, and the flurry of centennials that followed it. The 1889 centennial of George Washington’s inauguration in particular spurred the formation of the Daughters of the American Revolution. Its membership ballooned in the 1890s, and it did much to boost people’s recognition of patriotism and history.

So the “old” came to be treasured. But why the Gothic?

Oxford University (Mario Sánchez Prada/Flickr)American universities had always treasured the influence of Oxford and Cambridge. The colleges that would become the Ivy League were meant to model the Oxbridgian ideal of constructing a college around a quadrangle. In practice, though, American colleges of the 18th century were quite different. They were more devoted to scholarship than their British brethren. They were disconnected from a university. And they were poorer: Often, they didn’t have enough money to complete a ring of buildings around their quad.

During the 19th century, colleges constructed new buildings often without a central plan. An alumnus or his parents might give money for a new sciences building or museum, but with the donation came the ability to pick an architect. The 19th century was a hodge-podge of styles, reflecting whatever was popular that day or whatever struck a donor’s fancy.

During the 19th century, colleges constructed new buildings often without a central plan. An alumnus or his parents might give money for a new sciences building or museum, but with the donation came the ability to pick an architect. The 19th century was a hodge-podge of styles, reflecting whatever was popular that day or whatever struck a donor’s fancy.

Even as buildings began to aspire to something “Gothic, ” then, it was a decidedly ahistorical “Gothic.” Architects of the 12th and 13th century tried to solve an engineering problem: how to make a structure as tall as possible while minimizing load on the walls. They developed stained glass windows and flying buttresses as a way to build to these heights, then accented it with spires, pointed arches, and decorated portal programs.

“What Gothic meant changed depending on the time, ” Johanna Seasonwein, a fellow at Princeton University Art Museum, told me. When Victorians emulated Gothic, they did it sloppily, mixing styles and idioms. “Something Islamic, something Byzantine, ” might get thrown in there, says Seasonwein. This was the Victorian Gothic of the 1860s and ‘70s: a mishmash.

Collegiate Gothic, which followed Victorian Gothic, was much more precise. It emulated Oxford and Cambridge more directly.

There’s even a patient zero, of sorts, of Collegiate Gothic. In 1894, Bryn Mawr commissioned a new building, Pembroke. Its interpretation of Gothic so inspired other schools that they commissioned similar plans from the architects which designed the hall. (That firm, Stewardson & Cope, wound up constructing a near-copy of Pembroke on Princeton’s campus, where it’s called Blair Hall.)

Bryn Mawr’s Pembroke Hall, completed in 1894RELATED VIDEO

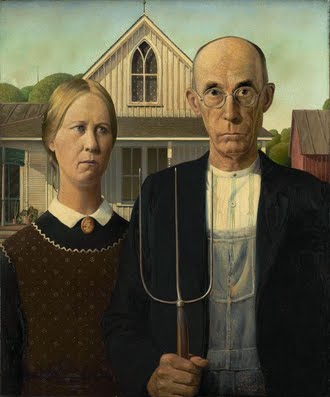

American Gothic is a painting by Grant Wood, in the collection of the Art Institute of Chicago. Wood's inspiration came from a cottage designed in the Gothic Revival style with a distinctive upper window and a decision to paint the house along with "the kind of...

American Gothic is a painting by Grant Wood, in the collection of the Art Institute of Chicago. Wood's inspiration came from a cottage designed in the Gothic Revival style with a distinctive upper window and a decision to paint the house along with "the kind of...

The Cathedral of the Nativity of the Blessed Virgin Mary, at 870 W. Howard Avenue in Biloxi, Mississippi, is the seat of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Biloxi.

The Cathedral of the Nativity of the Blessed Virgin Mary, at 870 W. Howard Avenue in Biloxi, Mississippi, is the seat of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Biloxi.