|

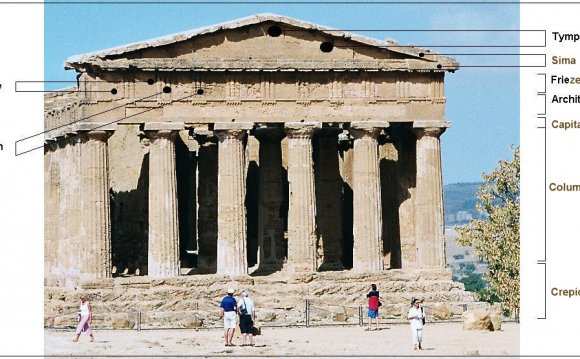

Legacy of Greek Architecture The legacy of Greek architectural design lies in its aesthetic value: it created lots of beautiful buildings. This beauty came not just from the grandeur and nobility of its architectural columns, but also from its ornamental features. The fluting of its columns, for instance, affords grace and vibration to the otherwise stolid shafts; but the channels reinforce rather than cut across support lines. The frieze is lifted above an architrave kept unadorned, preserving crossbar strength. The transitional members, capitals and moldings, agreeably soften the profile angles without loss of firmness. Supports are cushioned, but without undue softening. Just how great and distinctive are these achievements may be seen by contrast in Roman art when the insensitive Romans pick up the Greek elements and use them grandiosely and thoughtlessly, vulgarizing the ornamental features. Nevertheless, Greek ornament as a style of adornment in applied art was to be an overwhelming favourite in later ages, even down to the twentieth century. See also: Greatest Sculptors (from 500 BCE). Whatever the precise ingredients of Greek building design, Western architects have tried for centuries to emulate the finished product. During the 15th and 16th centuries Renaissance architecture embraced the whole classical canon, albeit with a slightly more modern touch - examples include: Dome of Florence Cathedral, S Maria del Fiore, 1418-38, by Filippo Brunelleschi - for more on this, see: Florence Cathedral, Brunelleschi and the Renaissance (1420-36) - as well as Tempietto of S Pietro in Montorio, Rome, 1502 by Donato Bramante. Meantime, Venetian Renaissance architecture featured numerous villas in Vicenza and the Veneto designed by Andrea Palladio (1508-80), who himself influenced the English designer Inigo Jones (1573-1652). Baroque architecture used Greek designs as the basis for many of its greatest creations (examples: St Peter's Basilica and St Peter's Square, 1504-1657, by Bernini et al; St Paul's Cathedral, London, 1675-1710, by Christopher Wren (1632-1723). Eighteenth century architects in both Europe and North America rediscovered Greek designwork in Neoclassical architecture (examples: the Pantheon, Paris, begun 1737, by Jacques-Germain Soufflot (1713-80); the iconic Brandenburg Gate in Berlin built by Carl Gotthard Langhans (1732-1808); the US Capitol Building, Washington DC, 1792-1827 by Thornton, Latrobe & Bulfinch; Baltimore Basilica, 1806-21, by Benjamin Latrobe; Walhalla, Regensburg, 1830-42, by Leo von Klenze). In nineteenth century architecture, Greek "Orders" were resurrected in both Europe and the United States through the Greek Revival movement. Even modern Art Nouveau architects like Victor Horta (1861-1947) borrowed from antique Greek designs. For long periods of time Western Europe and America accepted the belief that artistic practice, even in the machine age, must be based upon study of these classic "Orders." This was part of the neo-Hellenism which was a religion in Europe, so that even in the 1920s Sir Banister Fletcher - the renowned architectural historian - could write: "Greek architecture stands alone in being accepted as above criticism, and therefore as the standard by which all periods of architecture may be tested." (A History of Architecture: 6th Edition, 1921.) Ultimately, Greek architecture presents us with a concrete illustration of moral and spiritual truth. The solid foundation platform; the down-pressing mass of architrave, frieze, and roof-structure, counteracting the otherwise too powerful sense of lift, from the columns; the serenity of the colonnade, modified by the exuberance of sculptured frieze and pediment - all this may be seen as a tangible expression of the Greek combination of freedom and restraint, of perfectly poised aspiration and reason, of invention and discipline. The columns, some say, mark the rise toward truth or perfection; but the downbearing weight restores balance, caps the too aspiring lift. Thus Fate stops the too presumptuous human reach. This is the philosophical meaning of Greek architecture, which has entranced architects around the world for more than two thousand years. Famous Greek Temples DORIC Temple of Hera, Olympia (590 BCE)

Temple of Apollo, Syracuse, Sicily (565 BCE)

Selinunte Temple C, Sicily (550 BCE)

The Temple of Apollo, Corinth (540 BCE)

Temple of Hera I, Paestum (530 BCE)

Selinunte Temple G (The Great Temple of Apollo), Sicily (520-450 BCE)

Temple of Apollo, Delphi... |